(English below) L’Antropocene è stata proposta come l’attuale epoca caratterizzata da pressioni dell’uomo sulla biodiversità senza precedenti. Infatti, le stime più recenti riportano che quasi il 40% delle specie vegetali è minacciato di estinzione. L’estinzione di qualsiasi specie rappresenta una perdita di caratteristiche e risorse uniche e preziose, frutto di milioni di anni di evoluzione. Risulta quindi urgente intraprendere azioni di conservazione basate su solide ricerche scientifiche per arrestare, o almeno rallentare, questa tendenza.

In questo contesto, un complesso studio condotto da un gruppo internazionale composto da 32 istituzioni di tutto il mondo, coordinato dal Prof. Thomas Abeli e dalla Dr.ssa Giulia Albani Rocchetti del Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Università Roma Tre, in stretta collaborazione con l’Università di Pisa (Dr. Angelino Carta) e con l’Università di Pavia (Prof. Andrea Mondoni) ha studiato il potenziale di resurrezione di oltre 360 specie vegetali attualmente considerate estinte.

La maggior parte di queste specie è probabilmente persa per sempre. Tuttavia, potrebbe esserci una possibilità di recuperare alcune di queste specie. La scienza delle “De-estinzioni” si propone di sviluppare conoscenze e metodi per riportare in vita specie estinte.

Per quanto riguarda le piante, molte si riproducono per mezzo di semi che possono rimanere vitali per molti decenni o secoli e potenzialmente svilupparsi in individui adulti.

Esiste dunque la possibilità di riportare in vita piante estinte i cui semi sono conservati nelle collezioni naturalistiche, in particolare negli erbari (in effetti, se ci fossero dei semi vitali di una certa specie, questa può dirsi davvero estinta?). Questa ricerca rappresenta il primo passo mosso dal Prof. Abeli e dalla Dr.ssa Albani Rocchetti verso questa direzione e ha permesso di individuare circa 160 specie estinte di cui ancora esistono semi in oltre 60 erbari di tutto il mondo.

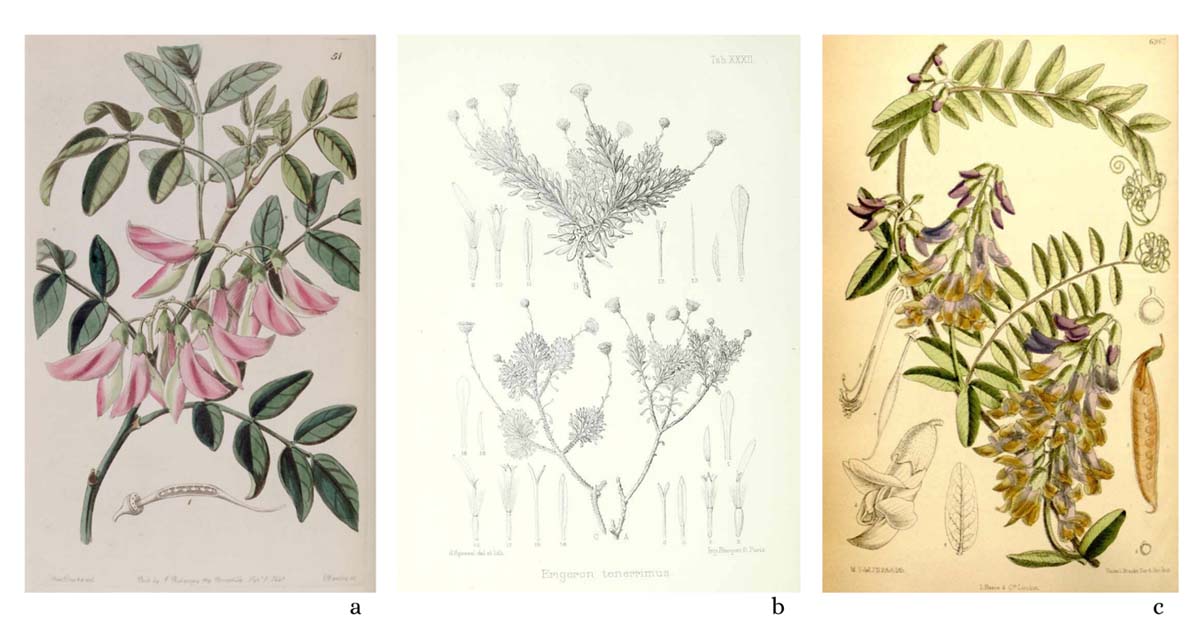

Hanno valutato questi “candidati alla de-estinzione” in base a criteri quali la resistenza dei loro semi alla conservazione, l’età degli esemplari e l’unicità evolutiva delle specie, generando un elenco di specie prioritarie candidate alla de-estinzione. Questo rappresenta una base di primaria importanza su cui avviare il futuro recupero di specie estinte. Tra queste spiccano diverse Leguminose (Fabaceae), come Astragalus endopterus dall’Arizona, Streblorrhiza speciosa dall’isola Norfolk e l’europea Vicia dennesiana, endemica delle Azzorre (Portogallo), note per la grande longevità dei loro semi.

Infine, la ricerca ha messo in evidenza i rischi e i benefici della recente proliferazione di database e aggregatori di dati, nell’era attuale della digitalizzazione e dei big data. Se da un lato questi strumenti hanno accelerato l’accesso ai dati sulla biodiversità, dall’altro lato possono velocizzare la diffusione di informazioni errate. Per esempio, nei casi in cui lo status di conservazione delle specie non sia aggiornato, le azioni di conservazione, in particolare per le specie gravemente minacciate, possono essere fuorviate.

In collaborazione con il Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI), il gruppo di ricerca ha identificato le incongruenze relative allo status di conservazione di specie vegetali in importanti database internazionali, scoprendo che ben 15 specie di piante considerate estinte non lo sono affatto, ma sono conservate in orti botanici o in natura.

Le informazioni raccolte hanno notevoli risvolti nell’ambito della conservazione delle specie, in quanto permetteranno di pianificare azioni specifiche di salvaguardia e reintroduzioni in natura per specie gravemente minacciate che sono state erroneamente dichiarate estinte.

I risultati di questa ricerca sono stati pubblicati sulla prestigiosa rivista «Nature Plants» in due articoli intitolati Out-of-date datasets hamper conservation of 7 species close to extinction (URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41477-022-01293-w) e Selecting the best candidates for resurrecting extinct-in-the-wild plants from herbaria (URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41477-022-01296-7).

[Immagine: Tavole botaniche di piante estinte. a) Streblorrhiza speciosa Endl. (Sarah A. Drake, 1841 in Edwards’s Botanical Register or Ornamental Flower -Garden and Shrubbery); b) Tetramolopium tenerrimum (Less.) Nees (A.R. d’Apreval in Drake del Castillo, E., Illustrationes florae insularum maris pacifici (1886-1892)); c) Vicia dennesiana H.C. Watson (M. Smith in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine in 1887, ser. 3, vol. 43).]

***

Are extinct plants lost forever? First steps towards resurrection

We are living in the Anthropocene – an epoch defined by unprecedented human pressure on biodiversity. Recent estimates suggest that almost 40% of plant species are at risk of extinction. The extinction of any species represents a loss of unique and valuable characteristics and resources shaped by millions of years of evolution. There is an urgent need for conservation action to halt, or at least slow, this trend, grounded in sound scientific research.

Now, a complex study carried out by an international group of 32 institutions, including XXX, coordinated by Prof. Thomas Abeli and Dr. Giulia Albani Rocchetti from the Department of Science, Roma Tre University, in close collaboration with the University of Pisa (Prof. Angelino Carta) and the University of Pavia (Prof. Andrea Mondoni), investigated the potential to resurrect more than 360 plant species currently considered extinct.

Many of these species are likely lost forever. However, for some there may be a possibility of recovery. The science of ‘de-extinction’ aims to develop the knowledge and methods to bring extinct species back to life.

Many plants reproduce by seeds that can remain viable, with potential to develop into adult individuals, for decades or even centuries. This raises the possibility of bringing back to life extinct plants whose seeds are preserved in natural history collections, particularly in herbaria (Indeed if viable seeds are found to exist, can the species be called extinct at all?). In a key advance, Abeli and Albani Rocchetti identified around 160 extinct species for which seeds still exist in more than 60 herbaria worldwide.

They scored these ‘candidates for de-extinction’ according to criteria including their seeds’ resilience to storage, the age of the specimens and the evolutionary distinctness of the species, generating a prioritised list of candidate species for de-extinction, a crucial foundation for future work to resurrect plant species from extinction. Among the top candidates are several species of the pea and bean family (Fabaceae), including Astragalus endopterus (the sandbar milkvetch) from Arizona, USA, Streblorrhiza speciosa (Philip Island glory pea) from the Pacific Norfolk Island group, and Vicia dennesiana (Dennes’s vetch), endemic to the Azores (Portugal), which are known for having great seed longevity.

This research also highlighted risks and benefits of the recent proliferation of databases and data aggregators in the current era of digitisation and big data. While these tools have accelerated access to biodiversity data, in some cases they can also speed the spread of erroneous information, for instance where species’ conservation status is not updated, conservation actions, particularly of highly endangered species, can be misled. Working with Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI), the team identified inconsistencies in the recorded conservation status of plant species among prominent international databases. They revealed that 15 plant species considered to be extinct are not extinct at all, but are maintained either in botanical gardens or in the wild.

The results of this study have considerable implications for conservation, providing tools to guide the first potential resurrection of extinct plant species and for planning conservation actions including reintroductions of highly threatened species that have been erroneously declared extinct.

This research is published two articles in the current issue of the prestigious journal «Nature Plants»: Out-of-date datasets hamper conservation of 7 species close to extinction (URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41477-022-01293-w) and Selecting the best candidates for resurrecting extinct-in-the-wild plants from herbaria (URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41477-022-01296-7).

[Image: Botanical illustrations of extinct plant species. a) Streblorrhiza speciosa Endl. (Sarah A. Drake, 1841, in Edwards’s Botanical Register or Ornamental Flower -Garden and Shrubbery); b) Tetramolopium tenerrimum (Less.) Nees (A.R. d’Apreval in Drake del Castillo, E., Illustrationes florae insularum maris pacifici (1886-1892)); c) Vicia dennesiana H.C. Watson (M. Smith in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine in 1887, ser. 3, vol. 43).]